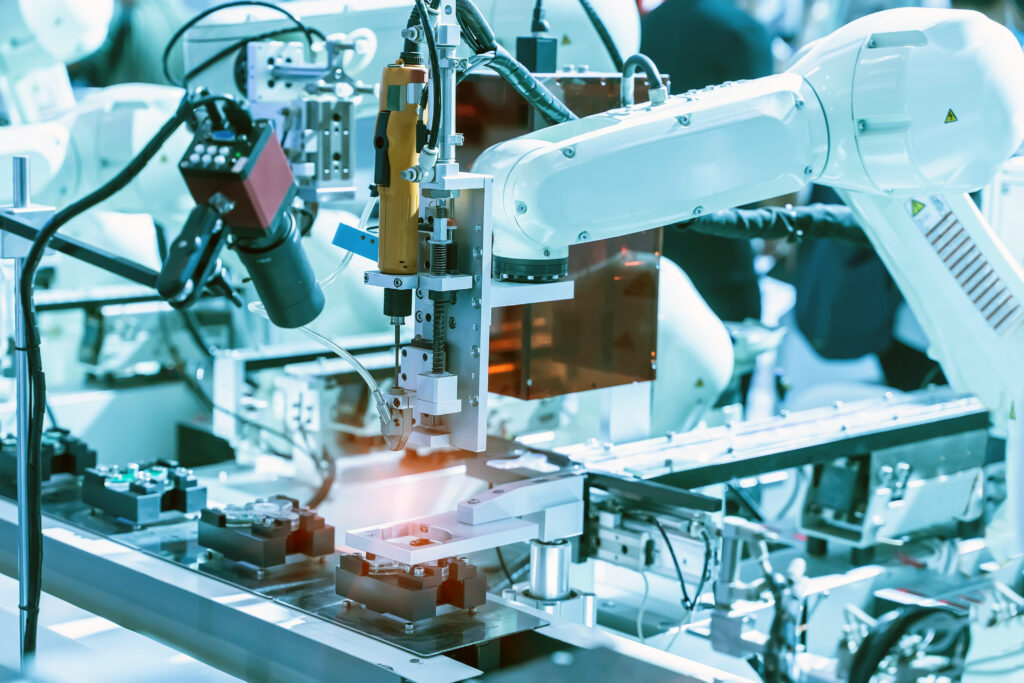

Garnering much attention these days are industrial robotics and their integration of motion components and incorporation into workcells with other motion-based automated equipment. Such robotic workcells also feature conveyors, vision systems, and machines to automate specific tasks.

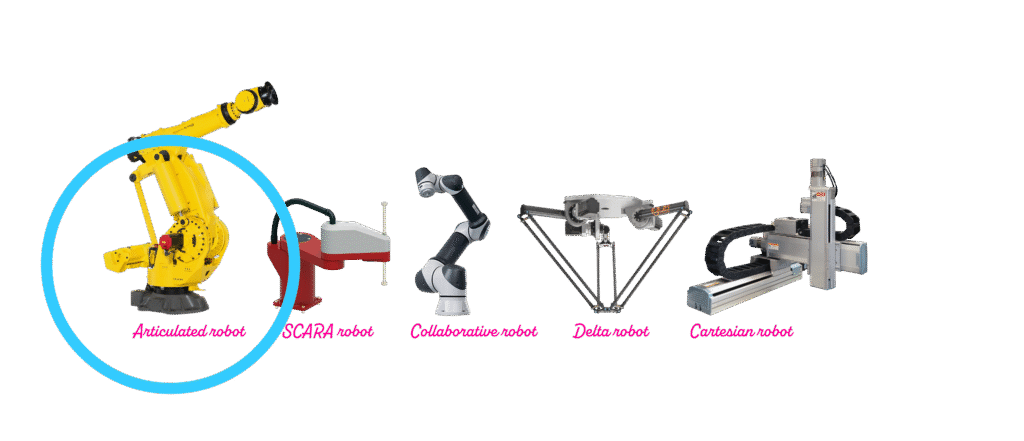

So, what makes a motion system a robot or machine? In other words, what’s the distinction between motion systems used in automated machinery and that taking the form of robots? The latter are capable of automatically executing complex and programmable (and especially reconfigurable) movement sequences. This definition is admittedly quite vague, and even the ISO 8373 definition could describe machines not usually considered robots. It says a robot is an “automatically controlled multipurpose manipulator” reprogrammable in three or more axes.

In contrast with robots, machines such as vending machines (to give just one example) are designed for a single well-defined use in a single fixed location. They can run tasks on different workpieces but aren’t likely to be reprogrammed for multiple purposes. Machines only serve the single well-defined use of dispensing purchased products.

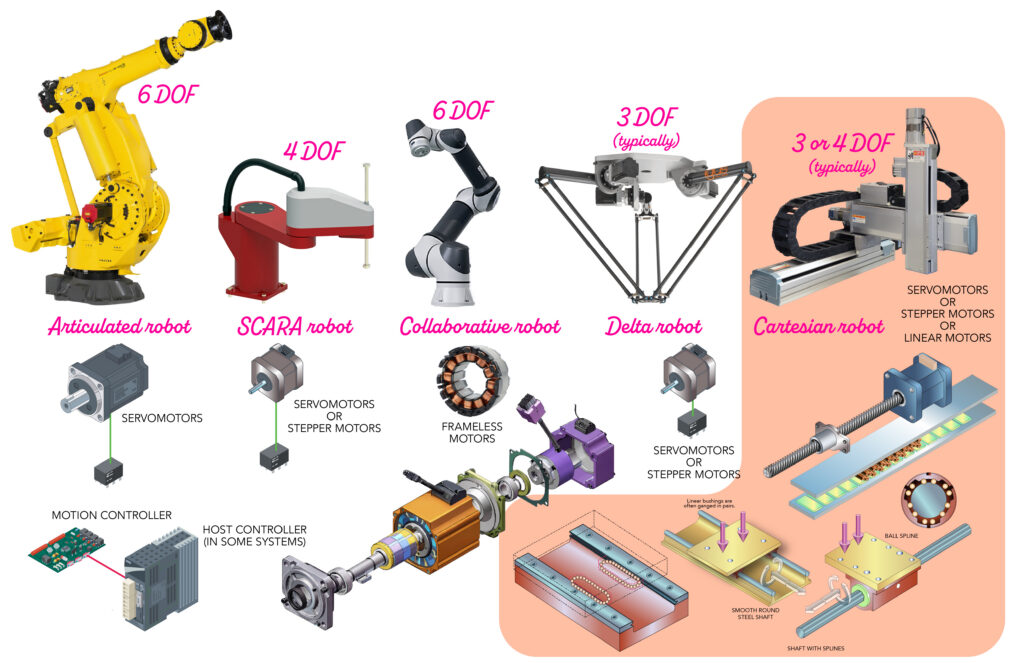

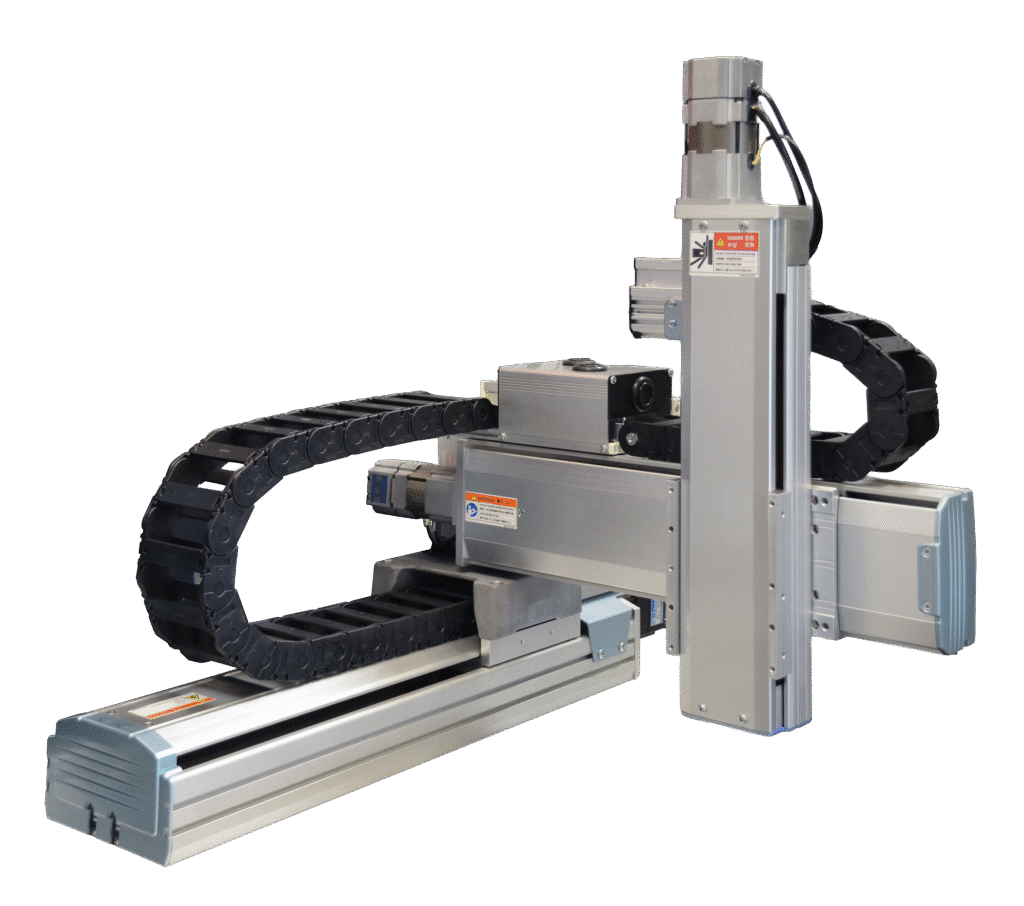

Robotics in the form of cartesian robotics also consist of assemblies of linear-motion components such as linear guides, ballscrews, and encoders … or pre-integrated actuators … or even linear motors as in the high-speed assembly shown below. But just like articulated and SCARA robotics, these are more likely to serve various adaptive functions.

Typical technologies for each robot type

In fact, some gears, motors, and controls technologies are common to articulated and SCARA robotics as well as cartesian systems. These stationary solutions (often what’s implied when ‘industrial robots’ are referenced with no other context) even share basic technologies with automated guided vehicles (AGVs). More information on AGVs can be found at therobotreport.com and designworldonline.com. But strategies differ for synchronizing multi-axis motion with robot kinematics.

Related: Leading motion-control and actuation options for robotics

Key is reducing latency, complexity, and cost for material handling, machine tending, and other setups featuring robotics alongside other types of motion systems.

Motion component suppliers = robotic suppliers

Related: The Robot Report — Motion control news

As robotics are just a subset of motion system designs, it’s no wonder that many motion-component suppliers offer completely pre-integrated robotic solutions of their own. Others support the design and integration of robotics with subsystems customized to robotic operations.

In fact, some suppliers offer motorized axes and motion solutions for every robotic type used in industrial applications. Granted, low-cost variations may prioritize use of engineered plastic components (also supplied separately) so not employable for all applications. That said, many of these solutions work in research, food and beverage, vending, consumer service, laboratory automation, and other cost-sensitive automation.

On certain approachable SCARA assemblies are stepper motors, belt drives, and a screw-driven vertical axis with plain linear guides.

Stepper motors (and especially closed-loop steppers) are also suitable for Cartesian and SCARA-style robots used in light assembly and laboratory automation — including PCB loaders and test-fixture robots. Closed-loop stepper motors (fitted with encoders) more often impart motion to joints of assemblies moving payloads to 3 kg or so — or to grippers, tool changers, vision mechanisms, or feed units on welding torches.

Down to the smallest components — including washers, spacers, shims, and fasteners. For example, these elements hold the assembly while preventing stack-up error that can cause binding, angular misalignment, or tool-center drift.

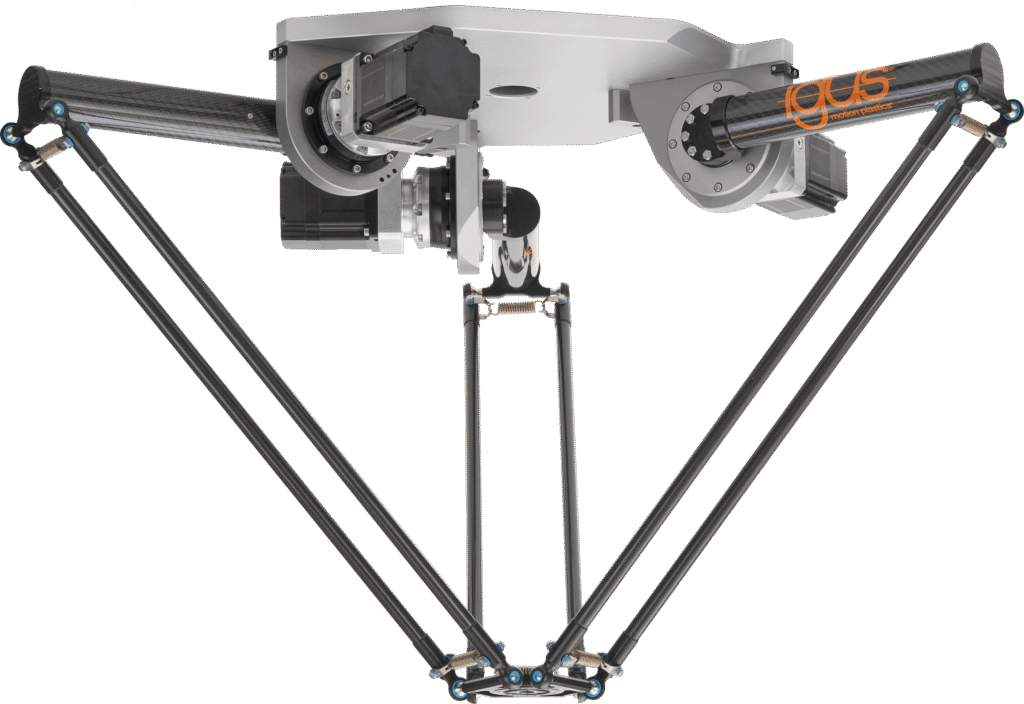

Delta robotics’ unique kinematics and dynamics

Delta or spider robots are their own breed with kinematics featuring NEMA stepper-based screw actuators … or belt drives on each linkage. Otherwise, many industrial-grade deltas (as for pick-and-place tasks) feature permanent-magnet servo gearmotors (with inline helical or planetary gearing) for each parallel linkage.

In the stainless delta robot shown below, linkages directly attach to servomotor output shafts. Gear ratios are low because the assembly itself imparts high dynamics.

View this post on Instagram

For gearing in delta robots, helical gearing minimizes vibration, but planetary gearing is especially power dense.

Six degrees of freedom (DOF) robotics

Articulated six-degree-of-freedom robotic arms are what most laymen picture when asked to conjure aa industrial robotic arm. These have linkages in series with work envelope constrained by the joints … and defined by the end effector’s maximum X-Y-Z reach along with θX, θY, θZ ranges.

It’s common to use shoulder-elbow-wrist analogies to reference degrees of freedom. A straightened elbow joint puts the wrist at its furthest from the base — and the end effector in a position of reduced usefulness. A bent elbow joint brings the end-effector closer to its base for more orientation range.

Articulated robots excel at maneuvering workpieces through nonaligned stations and surfaces.

For six-DOF robotics (as well as SCARAs that we’ll cover next) every joint has a set nominal repeatability. However, overall repeatability at the end effector depends on its position in space with furthest reaches having the worst values. So, workcell layout is best when objects are well within the arm’s reach and not requiring any joints to assume a fully straightened posture.

Selective compliance assembly robot arm (SCARA) robotics

SCARA robots are another type of articulated arm with linkages in series. These lead for pick-and-place tasks moving workpieces from one conveyor or another flat surface to another — especially if the workcell allows for the SCARA to be centrally positioned. They’re capable of modest to moderate throughput and where installation won’t justify lots of customization —insertion or press-fit functions, for example.

SCARAs can be procured as off-the-shelf three or four-DOF solutions … or the kinematics lend themselves to in-house builds. Another benefit: SCARAs (like other articulated robotics) often have convenient passthroughs for feeding power, encoder signals, I/O wiring, and pneumatic lines from the base to the end effector.

Industrial SCARA joints typically include ac servomotors with absolute encoders for position feedback even when main power is cut and restored. Encoders without batteries can help make the SCARA compact. Even more compactness (and reach envelope) is possible with a well-integrated joint stack — and a motor, bearing, and gear carrier having minimized axial length.

Planetary gearheads impart torsional stiffness and efficiency with compactness to fit within joints. There’s no elastic windup like that associated certain strain-wave gears. So, the controller can maintain high repeatability without aggressive compensation algorithms.

Also common are safety brakes at the extremity joints (J3 and J4). The Z axis (as in a typical Epson robot) uses a ballscrew with ball spline. The igus example (below) is a little bit different … it has a belt-driven Z axis featuring two linear guides.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.