Switched-reluctance motors have many advantages, including low cost and low energy use. However, their main drawback is they are difficult to control. This is for a variety of reasons.

Switched-reluctance motors have many advantages, including low cost and low energy use. However, their main drawback is they are difficult to control. This is for a variety of reasons.

Namely, they need highly accurate position tracking, the inductance in the motor changes with the degree of alignment of their poles; they require unipolar drives, and they tend to produce much audible noise.

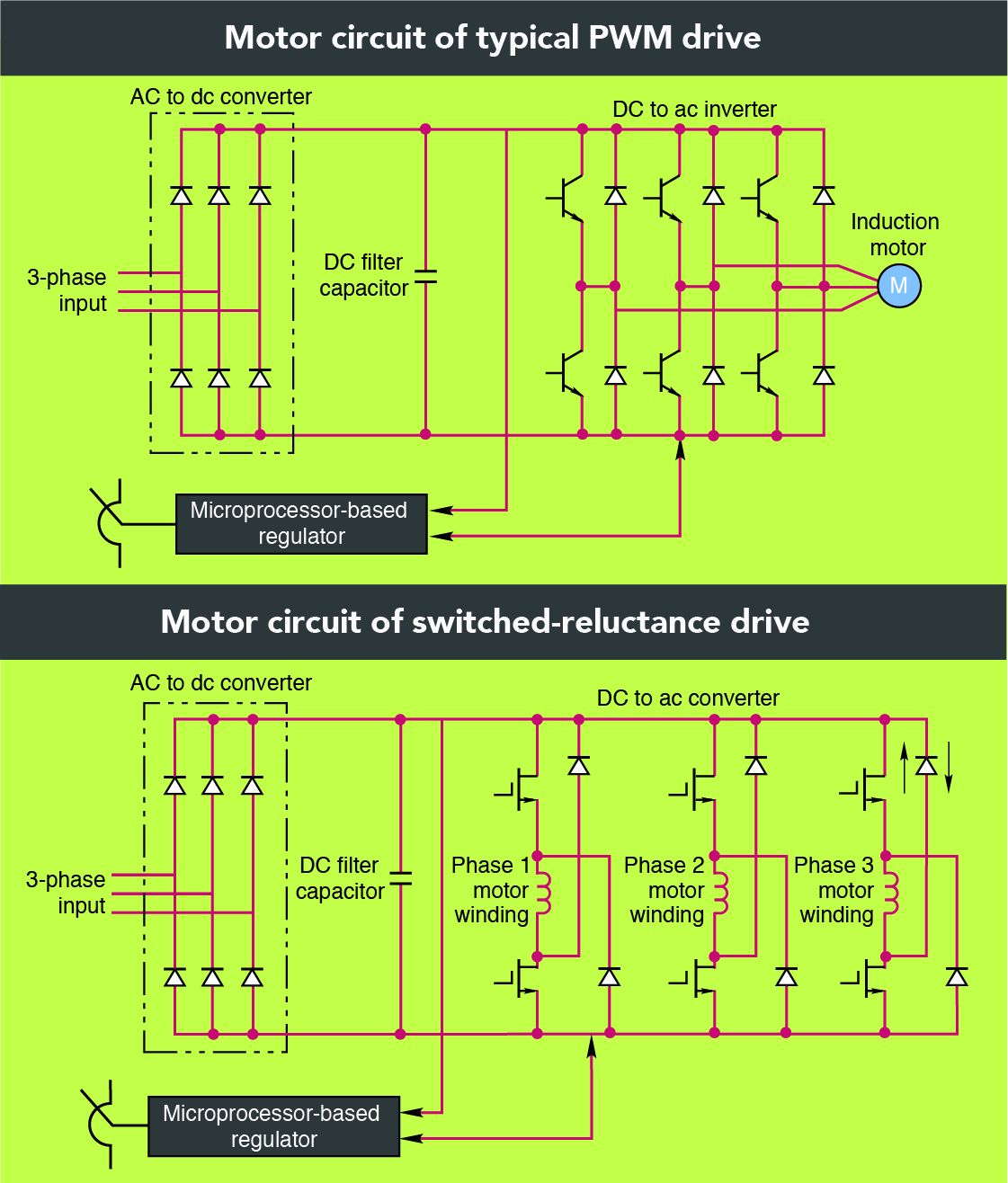

The drive for an SRM must be unipolar. This means each phase needs to complementary switch and diode choppers. This means twice as many components. While conventional steppers can come in both unipolar and bipolar configurations with drives for both setups, SRMs have no such options.

The changing induction of the motor is another concern. Because of the way a switched reluctance motor operates, with changing reluctance comes changing inductance. Thus, as the motor rotates, the inductance in the stator’s windings changes. This means sending the correct amount of current to each winding is difficult, as the exact amount to send is constantly in flux. Because of the changing induction, torque fluctuations are a concern as well. This can lead to vibrations or even negative torque, or even power regeneration when it is not needed or desired.

Because the inductance is constantly changing, the position of the rotor must be accurately tracked to compensate for this. This is so the drive and controller can handle any potential regenerated energy and compensate for torque fluctuations. Accurate position tracking introduces more components into the system and necessitates a feedback loop.

Audible noise is another control difficulty that SRMs face. Some noise comes from the vibrations and torque ripples, but another source is present. That being the stator and rotor are attracted towards each other due to the magnetic forces between them. This occurs in every pole as the rotor turns. Often this is solved in two ways; one is to simply make the stator more robust, using thicker materials that are less flexible. This introduces expense and weight, however. Another is to track the position of the rotor and activate a coil opposite from the currently active pair with a small amount of current to offset the attractive force. This again requires accurate position tracking, however.

These control difficulties may make it seem like SRMs are non-starters in many applications. However, as technology improves and newer control methods develop, switched reluctance motors may become a much more viable option Read: FAQ: How could drives soon make switched-reluctance motors more common? for more on this.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.