Sensors are machine edge devices, so are on the front lines — often completely exposed to the worst of what automated assemblies endure. In a recent Design World interview, Banner Engineering global business development manager for sensors Dana Holmes answered several questions about sensor survival in these harsh environments. Here’s what she had to say.

Eitel • Design World: Tell me about sensors for harsh environments.

Holmes • Banner Engineering: Harsh environments can imply a washdown environment in the food and beverage industry, or it can just mean a setting subject to vibration or temperature swings. But when engineers refer to extreme environments, they typically mean washdown-type settings — as that’s where most end users need rugged sensors. We manufacture sensors aimed specifically at satisfying specific IP ratings needed for these environments. Some of our sensors also include features to support hygienic conditions — to prevent debris buildup and the growth of bacteria. We also put potting material inside certain sensors to help them withstand temperature cycling.

Eitel • Design World: What kind of features are these — smooth surfaces or special housing plastics?

Holmes • Banner Engineering: Component materials are key to surviving these environments, as end users will sometimes use chemicals to aid in the cleaning of equipment. Stainless steel withstands exposure to many such chemicals, but not all of them. Other metals can corrode in chemical environments — and some plastics even melt.

Eitel • Design World: Where can design engineers learn about which materials work where?

Holmes • Banner Engineering: We publish chemical-compatibility information on the data sheets. One common issue is that design engineers and OEMs know little about the environments where these sensors will ultimately be installed. In contrast, it’s easy for end users to describe application settings — because they know exactly what their personnel are using. That means in most cases they can even provide us with a list of chemicals and say, “Here is what my facility uses” and sometimes more importantly, “Here are the concentrations we use.” A 20% concentration of a chemical might be fine for a certain plastic, but 30% will make it erode.

Eitel • Design World: That’s interesting.

Holmes • Banner Engineering: It is. A related issue is that customers will often tell OEMs, “Our machine isn’t going in a washdown area, so don’t worry about that” or say, “This design will never come in contact with chemicals.” But the next thing you know, we’re getting a melted product back because it did indeed come in contact with chemicals.

Eitel • Design World: Would you describe a nasty setting — or a product that came back damaged from an extremely challenging environment?

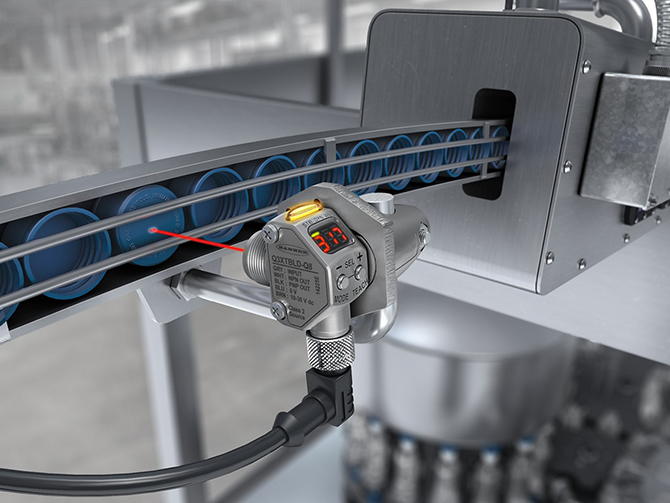

Holmes • Banner Engineering: I just visited a case-packer OEM. Their customer was using their equipment to pack bottles into cartons. The end user told the OEM, ‘There won’t be any material spilled, as it’s a completely dry environment — it’s fine.’ So the OEM installed standard metal Q3X laser contrast sensors as well as some plastic sensors on the application. Well, what the end user didn’t mention was that the capper wasn’t working very well, and the material they were putting in cartons was actually bottles of hydrochloric acid — a 30% solution of hydrochloric acid. When bottles came down the conveyor, they were spilling hydrochloric acid all down into the machinery. Next thing we know, the lenses on some of the sensors melted, because they’re made with plastic and not meant for that type of environment.

So we had to go back and swap the sensors to fiber-optic variations that are Teflon-encapsulated. Such sensors can survive that 30% solution, as can select plastic sensors and lenses. We and the OEM just needed to know more about the actual application.

Eitel • Design World: When you say ‘encapsulated’ do you mean the sensor body is filled with a silicone resin?

Holmes • Banner Engineering: We cover the sensor with Teflon — to act as a protective sleeve that goes over the tip of the fiber-optic assembly.

Eitel • Design World: Talk a little about what actual sensing functions work in harsh settings.

Holmes • Banner Engineering: Photoelectric sensors are a strength of ours, and they excel in many situations … but rely on light to function. So wet settings or places where material will collect on lenses are challenging. Such manufacturing environments can be served better by ultrasonic technology.

That said, photoelectric sensors employ visible red LEDs or infrared LEDs … and the latter actually does better in steamy-type environments. That’s especially true in opposed mode sensors with a lot of power, they aren’t affected by large water particles in the air of a steamy environment. These sensors essentially burn through that volume better than traditional options.

Eitel • Design World: Anything else that we should mention about extreme environments?

Holmes • Banner Engineering: We ask end users to really understand what’s happening in the environment and share as much as possible about that — so we can help get them into the right product. On the hydrochloric- acid application, we could have designed around that substance upfront — and avoided failures.

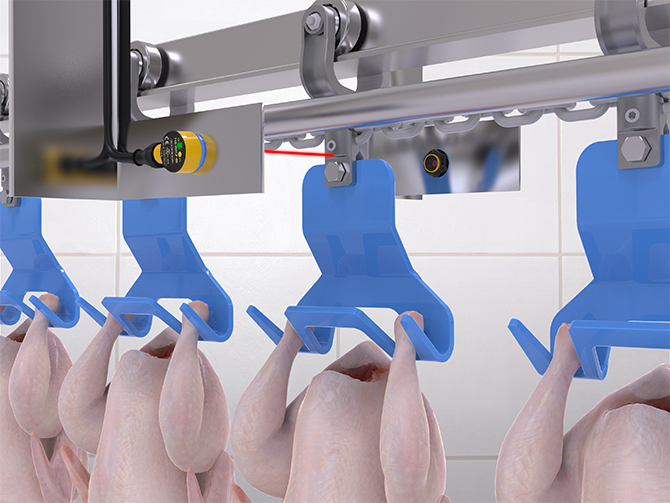

Settings with temperature cycling — as in dairy or meat processing plants — are also unique. Rooms must stay cold to keep product safe and fresh. But after product goes through, all equipment gets a washdown with hot water. That means machinery goes from very cold to very hot — which can cause condensation as well as thermal expansion and contraction. Some sensors handle this better than others. For example, thermal cycling on metal and plastic joints is pronounced because the materials expand and contract at different rates. That means there can even be openings in those joints — allowing water ingress. So design engineers must be cognizant of this.

We manufacture very rugged sensors to survive extreme temperature swings — in some cases, ultrasonically welding polymer sensor halves together so they have a monolithic body that will always stay impenetrable during thermal cycling.

Thermal cycling is also a challenge in how it causes condensation inside sensors. For these applications, we’ll fill the sensor with epoxy — so there’s no air on the inside to condense and interfere with the sensor optics.

High-pressure spray during washdown is another challenge. Some end users call IP67 washdown, while for others washdown is IP69K. It’s key to understand washdown definitions — and the difference between machinery that gets wiped off and machinery that gets hosed down with no pressure. These situations necessitate IP67 products. But if a machine takes rigorous cleaning with high-pressure high-temperature spray, that machine will need IP69K product.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.