Unlike typical static or dynamic loads, forces due to vibrations are difficult to predict, model, and account for when designing motion control systems. Some manufacturers recommend adding a safety factor to account for vibrations when sizing and selecting components — especially those that involve rolling or sliding motion, such as linear guides and screws.

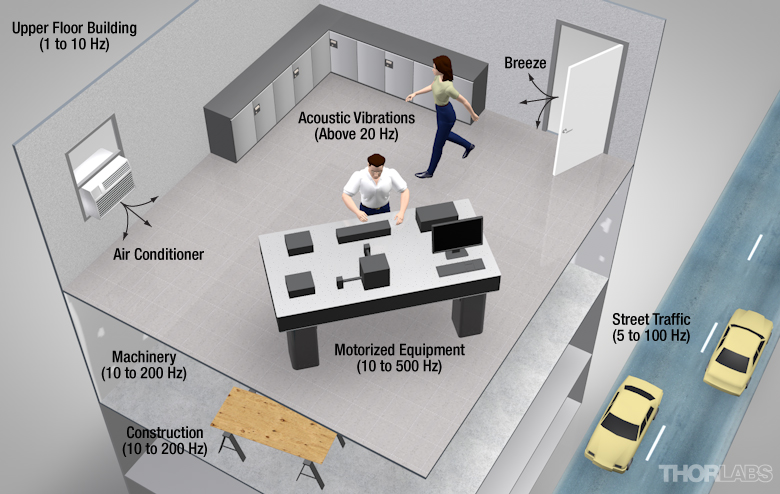

Of course, the ideal solution would be to avoid or remove vibrations altogether, eliminating the risk of damage to the equipment or interference with the process being performed. But avoiding vibrations is difficult since they can be caused not only by the machine or the nature of the process itself but also by structural resonances (vibrations of the building or supporting structure close to its natural frequency). For vibrations in machinery that cannot be avoided or eliminated, there are two methods to reduce their effects — vibration damping and vibration isolation.

Image credit: Thorlabs Inc.

Damping vs. isolation: Although the terms “vibration damping” and “vibration isolation” are often used interchangeably, they refer to different methods of vibration mitigation. Vibration damping is the process of absorbing or changing vibration energy to reduce the amount of energy transmitted to the equipment or machinery, while vibration isolation prevents energy from entering machinery.

Regardless of whether you’re discussing damping or isolation, the systems used to achieve the end result can be classified as either passive or active. Passive and active methods of vibration damping (or vibration isolation) differ in the way they respond to and manage vibrations. An easy way to distinguish between the two is that passive systems use simple mechanical devices, fluids, or elastomeric materials, whereas active vibration damping relies on a closed-loop system with feedback.

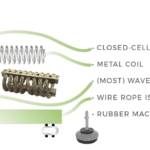

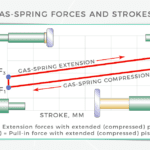

Passive vibration damping systems often employ a mechanical device or a fluid to reduce vibration, but passive damping can also be achieved with viscoelastic materials. In either case, the kinetic energy of the vibration is converted to heat. Because many types of damping systems have inherent resonances, they are primarily effective at frequencies higher than 4 Hz. Passive vibration dampers also tend to have trouble compensating for vibrations that occur in more than one direction — in other words, they are most effective for vibrations that occur only in the X, Y, or Z direction, and less so for vibrations that occur in multiple directions simultaneously.

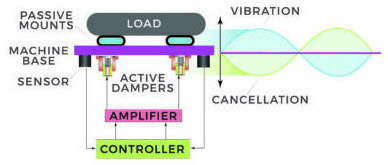

Image credit: Newport Corp.

Active vibration damping systems use added power in the form of electronically controlled sensors and actuators in a closed-loop system to counter vibrations and end oscillations. Unlike passive systems, active vibration damping systems can be tuned to remove resonances, allowing them to work at lower frequencies caused by structural resonances. They can also provide damping for vibrations and interference caused by the equipment itself, such as noise from cabling or acoustic noise.

Active systems can also provide proactive (rather than merely reactive) damping response by using feed-forward control. Where standard closed-loop configurations provide equal but inverse forces to cancel vibrations that enter the system, the addition of feed-forward allows the system to proactively generate and send canceling signals based on the expected vibrations. Feed-forward systems are especially useful for extremely low frequencies.

The choice between a passive or active vibration damping system should take into consideration how sensitive the machine or process is to vibrations — for example, vibrations are more detrimental to test and measurement equipment than to industrial production machinery — and the types of vibration that could occur.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.