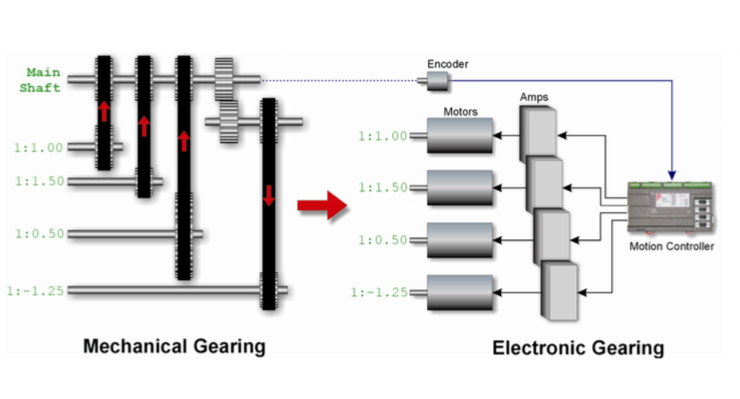

Gears are often used to establish a fixed speed relationship between a motor and a drive system (such as a ball screw, rack and pinion, or belt and pulley system). For example, when a belt and pulley system is connected to a motor through a 3:1 gearbox, each full rotation of the motor causes the pulley to turn 1/3 of a full rotation. Or, stated another way, the pulley turns 1/3 as fast as the motor does. Physical gearing is often used to help achieve the desired inertia match between the motor and the load. It can also help the motor produce the required torque for the application. Electronic gearing is based on a similar principle to physical gearing, but is done electronically, without mechanical linkages that can introduce backlash and degrade positioning accuracy of the system.

Image credit: Trio Motion Technology, Ltd.

With electronic gearing, there is a slave (or follower) axis, which is the axis being controlled, and a master axis. A key point to electronic gearing is that the absolute motion of the follower is not defined. Rather, the follower’s motion is specified in terms of a ratio based on the master axis’ motion.

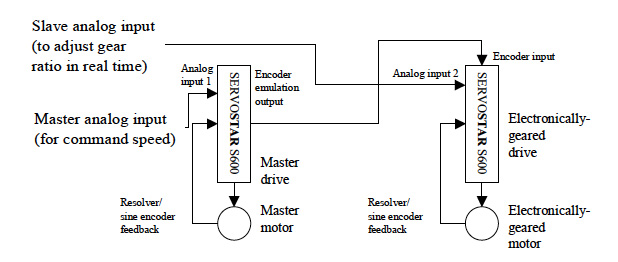

The premise behind electronic gearing is fairly simple: the master axis’ motion is measured—typically by the motor’s encoder—and this output becomes the input for the follower’s drive. The follower’s move is a function of the master’s move and the gear ratio, which defines the change in the follower’s position relative to the change in the master’s position.

Alignment between the axes is referred to as phase. Before electronic gearing was available, each motor was driven with a separate motion profile, and small errors that occurred in each axis caused them to deviate from each other. The only way to correct these alignment errors was by manually adjusting the axes. In electronic gearing, a “phase shift” command can be used to correct alignment errors between the master and the follower, without affecting the gear ratio. If the amount of correction can be predicted, it can be programmed as a preset phase shift move.

One advantage of electronic gearing is that the gear ratio can be changed as needed with a simple programming change, and can even be programmed to change within a move profile. This is an advantage over mechanical gearing, where adjustments to the gear ratio require mechanical changes, which are costly and time-consuming.

Image credit: Danaher Motion

Another advantage of electronic gearing is that one master can control many followers, as long as the master has the current available to drive all of the inputs to the followers. And each follower can be driven at a different ratio relative to the master. It’s even possible to connect electronically geared servos in a chain configuration, where one motor acts as a master to one axis and is a slave to another axis.

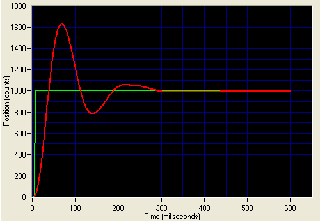

When electronic gearing is used, the tuning of the follower motor has increased importance. If the follower motor has a slow response time, it won’t accurately respond to the input signal from the master. To prevent this, the servo gains for the follower axis should be set as high as possible. Velocity feed-forward should also be set high to help reduce following error.

Electronic gearing is often used in precise assembly processes that are carried out by a robot following a conveyor, which requires that the robot’s speed and position be “locked” to the conveyor’s movement. Applications that involve two separate linear or rotary components moving in synchronization, such as winding, printing, and web tensioning, also benefit from electronic gearing and, specifically, from the ability to vary the gear ratio electronically, without requiring downtime to adjust the gear ratio manually.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.